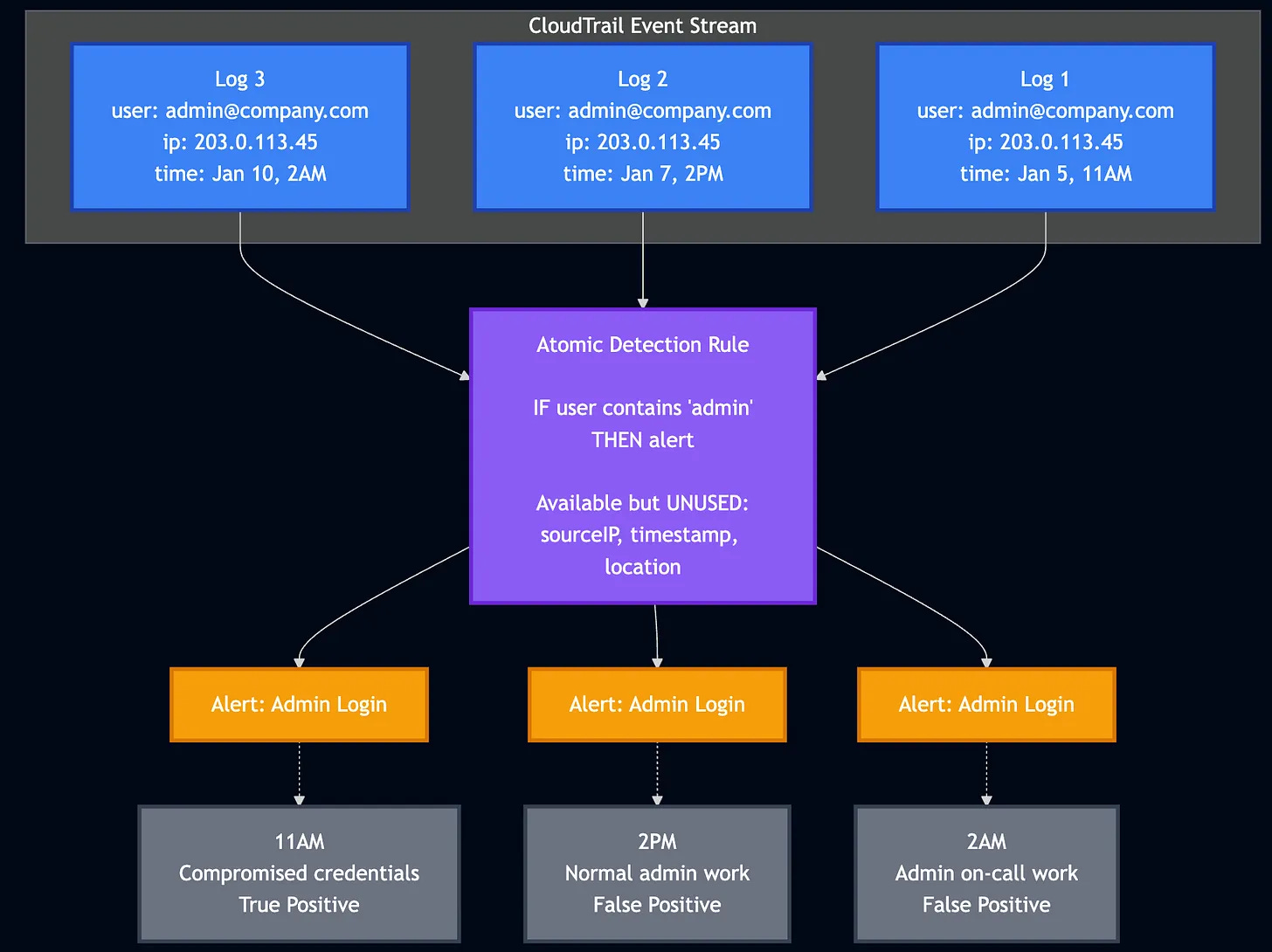

Atomic Detection rules are critical building blocks for a detection engineering function. They provide visibility into singular event or indicator-based threat activity within an environment. The rules are narrow in scope and generally lack context for the blue teamer’s environment and the threat actor performing the malicious action. For example, an atomic detection rule can inspect Administrator logon activity in a cloud environment and generate an alert whenever an Administrator logs in. This captures malicious admin compromises (high recall), but also triggers on every legitimate admin login (low precision), flooding analysts with false positives.

This tradeoff also works in the opposite direction on the precision-recall spectrum. A detection engineer can deploy an atomic rule that is so precise it becomes brittle. It may never generate an alert because the fields it tries to capture are so specific that they offer low operational value.

The answer to combat these types of detections is to increase the context around the attack itself. This means capturing more threat activity to group atomic detections together, as well as increasing the context of the environment to differentiate benign and malicious activity. Composite detections, also known as correlated or stateful detections, increase the context and, therefore, complexity of writing and maintaining the rule.

This field manual post covers (ha!) the pros and cons of composite detection rules and begins to explore strategies to expand context around threat activity.

Detection Engineering Interview Questions:

What is the MITRE ATT&CK?

What is a composite detection rule?

Explain a threat activity scenario where a composite detection rule helps reduce false positives?

How do composite rules increase operational complexity for a detection engineer?

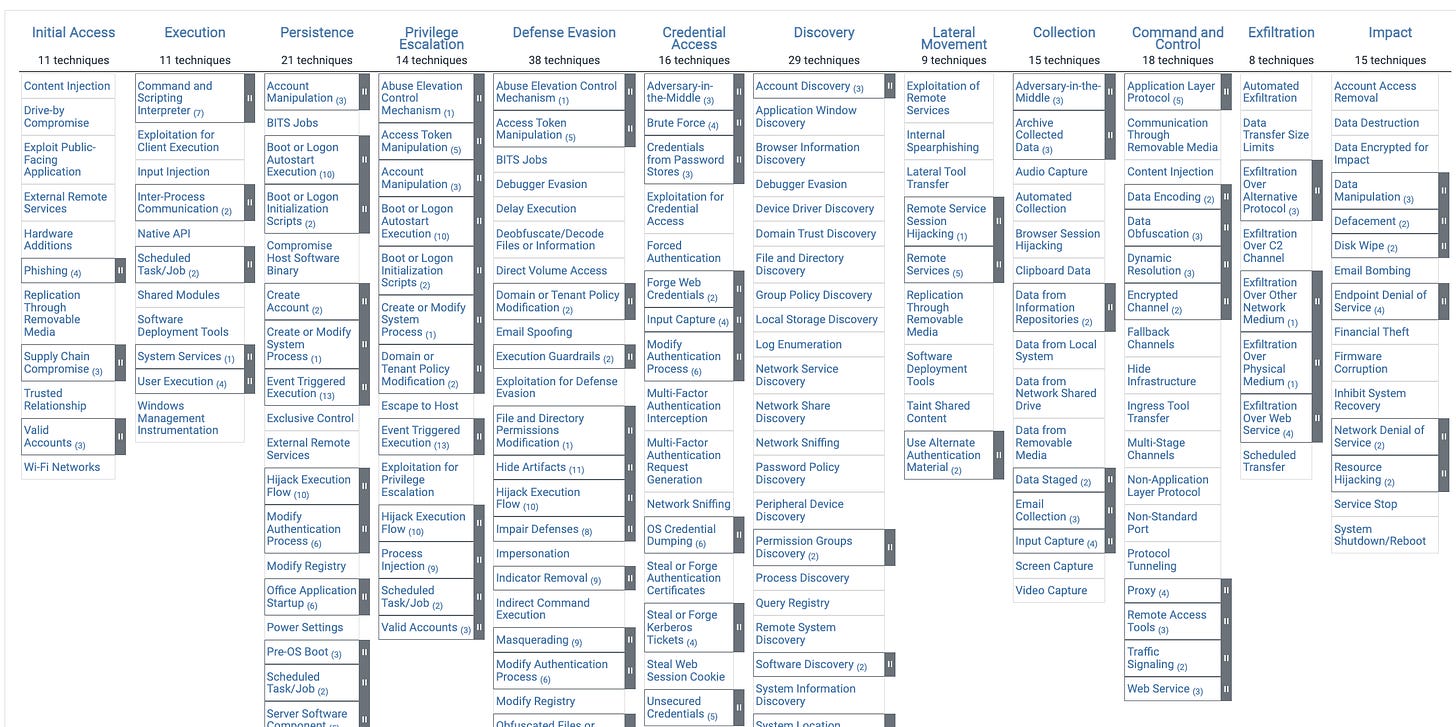

MITRE ATT&CK

MITRE ATT&CK (pronounced “MY-ter AT-ack”) is the industry standard for modeling threat activity. According to their main website:

“MITRE ATT&CK® is a globally-accessible knowledge base of adversary tactics and techniques based on real-world observations. The ATT&CK knowledge base is used as a foundation for the development of specific threat models and methodologies in the private sector, in government, and in the cybersecurity product and service community.”

There is no modern detection engineering and incident response without MITRE ATT&CK. It serves as a lexicon for security engineers across red and blue teams to standardize on how a specific attack occurs and the telemetry it generates.

Tactics are along the X axis and represent the stages an attacker traverses to achieve an objective, such as exfiltrating sensitive data, deploying ransomware, or causing a denial-of-service attack. Ransomware deployment is the end goal, but it requires a lot of steps to achieve that impact. For example, getting access to a victim machine, laterally moving to a domain controller, collecting secrets and cracking administrator passwords, and finally finding a way to deploy the ransomware.

The Techniques are the Y-axis under each Tactic. Techniques are the how: specific methods adversaries use within each tactic to achieve their objective. For example, Network Share Discovery under Discovery is used by attackers to find interesting files, folders and target machines connected to the current machine. They can leverage this to perform Collection of sensitive information and perform Lateral Movement to a higher privileged victim machine.

The beauty of MITRE ATT&CK is that it directly contradicts the adage “attackers only need to be right once, defenders have to be right 100% of the time.” Each technique listed above has associated telemetry, detection opportunities, and some even have threat groups that leverage the documented techniques.

What does this have to do with Composite Detections?

In my last post on Atomic Detections, I talked about how Atomic Detection rules lack context. These rules can use threat intelligence, such as malicious IP addresses, to generate alerts, but those IP addresses can be rotated, making the rule very noisy. So you wouldn’t want to write that rule unless it existed in the same window where the IP address remains malicious.

On a separate Atomic Detection rule, a detection engineer can write a rule to alert on Network Share Discovery. This is an obvious choice from my example before: the next logical step after Network Share Discovery is Lateral Movement. We want to detect that, right?

The problem here, again, becomes context. What if a legitimate process, such as a File Search or Data Backup tool, performs Network Discovery? You generate an alert, block the activity, and just killed productivity or a critical business process for one of your users. Does this mean you need to painstakingly investigate every Network Discovery alert? You could, but you would burn out, and the operational costs would be too high.

This is where Composite Detections can help, and where MITRE ATT&CK enables context via chains of events. By correlating Network Share Discovery with subsequent Lateral Movement attempts, we filter out benign activity and surface actual threats.

Composite Detections Tell a Story

Let’s continue to challenge the adage “attackers only need to be right once, defenders have to be right 100% of the time.” We know that writing one Atomic Detection rule can be noisy. So what if you write two? What if you write these rules across every single path along MITRE ATT&CK, under every Tactic? You would have high recall, but terrible precision, and a flurry of alerts that can’t discern between benign and malicious activity.

Let’s look at an example from our previous post on Atomic Detection Rules:

In this scenario, the Atomic Detection rule fires on administrator login activity. We are only looking at the event and ignoring sourceIP, timestamp, and location. These can help tell the story, but the story stops on the singular event. You could write some additional enrichment to tell the story that:

The Admin is logging in from a risky location, let’s say outside the U.S. for the sake of example

The Admin is logging in past business hours

But these enrichment points can also be part of legitimate business activity. This is where context comes into play.

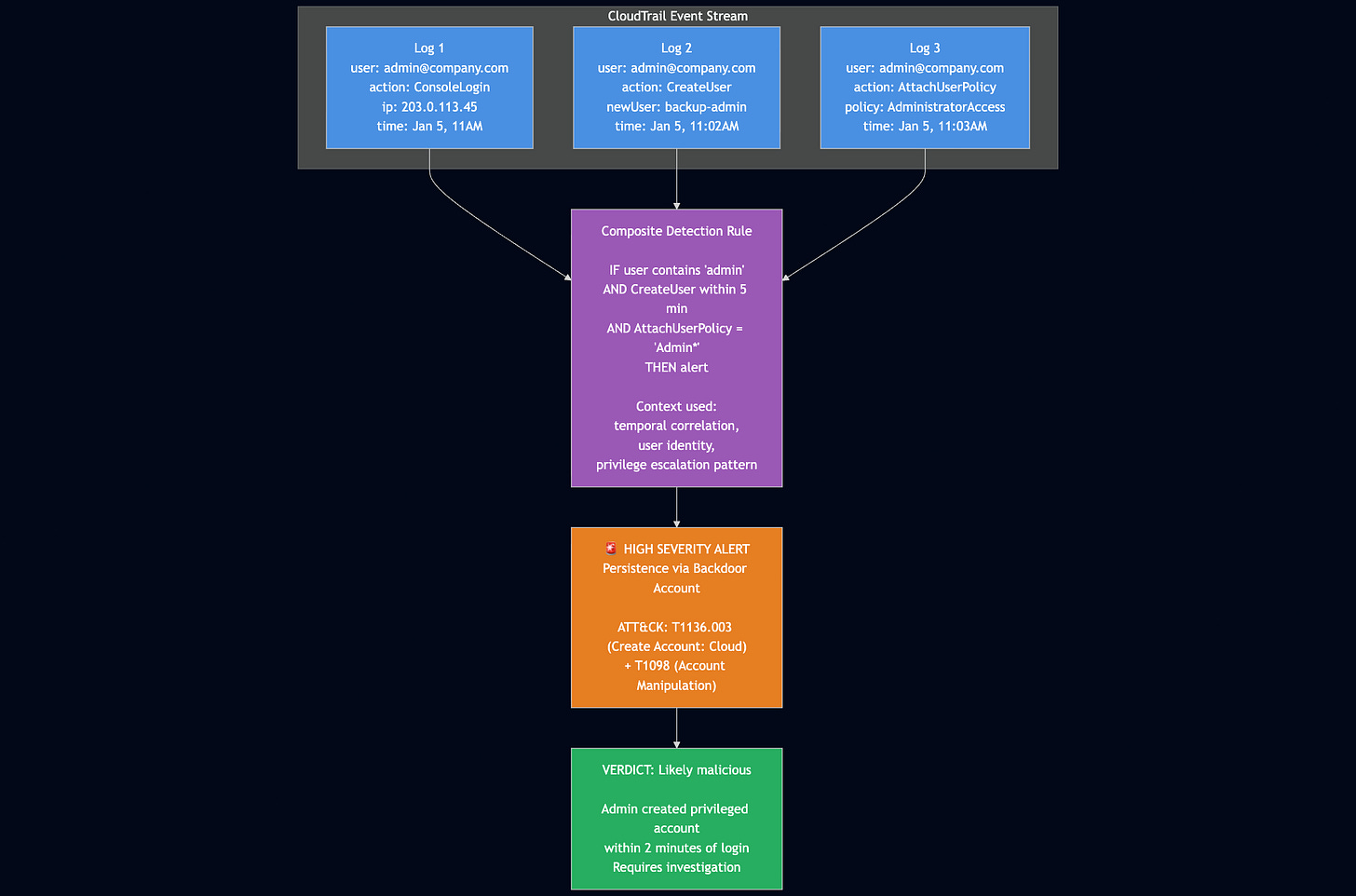

Let’s say you have two other rules that capture potential threat activity of an Administrator creating a second account and attaching an Administrator policy or profile to it. It’s riskier (it’s further along the ATT&CK chain), but it lacks context. But what if you combine the threat scenarios and create a story?

Here’s the story: an Administrator account gets compromised, and an attacker runs a script to log in to your AWS portal automatically. They are smart cookies and believe in another adage, “two is one, and one is none,” and create a second account to achieve Persistence on your account. They then leverage their Administrator privileges to attach an Administrator policy. Smart, if you reset the original Administrator password, they have a backdoor back into your environment!

By combining the three scenarios via the following rule, in pseudocode:

if user contains 'admin'

AND CreateUser action is called

AND AttachUserPolicy is called and the Policy = 'Admin'

THEN alert

You’ve told your SIEM quite a compelling story to look out for, and it found it!

There are some key questions from the above rule, and they emerge from the other data I’ve omitted from my diagram:

What is a legitimate amount of time between logging on and calling CreateUser?

Is calling CreateUser then attaching an Administrator policy malicious?

Does this Admin typically CreateUser and attach policies?

These questions are what adds complexity and cost to writing and maintaining a ruleset. So, a detection engineer must weigh the cost of this complexity versus the cost of false positives from Atomic rules.

In this specific Composite rule, we used Windowing. Windowing is a technique in which we capture activity in time windows and assume that any Composite detection that captures events within that window must be the result of threat activity. The rule assumes that if an Administrator account logs in, creates a secondary account, and attaches a privileged policy to it, it must be malicious. This reduces false positives by:

Combining three Atomic rules into one rule

Creates a story where these three actions together means something malicious is happening, or requires investigation

Assumes threat actors will try to do this quickly as their access may be revoked within a few minutes

Stories increase complexity

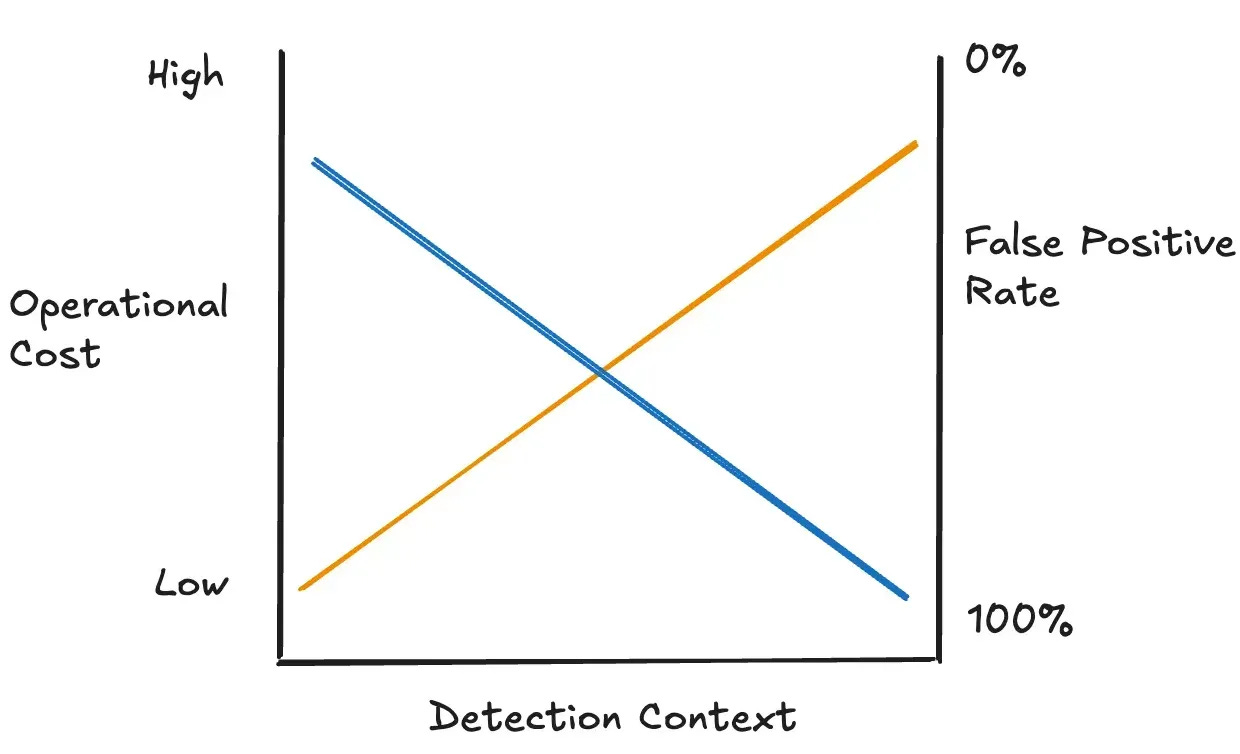

I linked a chart in my previous post about the trade-off between context, operational cost and false-positive reduction.

In this Windowed Composite Detection Case, there are several costs that detection engineers incur:

Does my SIEM technology support Windowing?

Does the combination of these detection rules capture the threat activity that I want? For example, should I also have a separate atomic rule for CreateUser to catch persistence attempts that don’t fit the 5 minute window? This can lead to false negatives if you only rely on composite rules.

Does the window period give me the best value? If I increase it to 15 minutes, what costs do I incur on server usage, indexing and other infrastructure components?

I will say that Detection Engineers I’ve hired, worked with, and spoken with at other companies spend as much time researching cost trade-offs as they do performing pure security research. This is the Engineering component of threat detection, and to me, these types of problems are what make the field exciting. You are part security researcher, part engineer, and part data scientist!

Conclusion

Composite detections shift detection engineers’ focus to reduce false positives by creating stories of attack chains. MITRE ATT&CK is the de facto industry standard for documenting how an attacker progresses through a breach to achieve an objective. Detection engineers can use ATT&CK to build atomic and composite rules to capture threat activity.

Atomic rules lack context by design, but when combined with other atomic rules via composite detections, you can start building a story of an attack. This story is the context you want to decide on whether you should investigate an alert. This story also reduces false positives by capturing the logical progression an attacker may take in your environment, and reduces the likelihood of alerting on benign activity.

The complexity of creating and maintaining composite detections stems from technological capabilities, such as windowing, as well as the hidden costs of assumptions made by the detection engineer. For example, combining three distinct events into a composite detection may miss other alerting scenarios within those events, leading to a false negative.

In the next Field Manual post, we'll explore different alerting mechanisms for composite and atomic detections outside of windowing.

Yessssssssss, all about the stories. When initially building RBA, I could show a story of detections to an analyst, a manager, or a director and they could immediately grok the tale of compromise, and then it was all about panels+actions that helped confirm/deny each piece of the story quickly for the day to day benign positive stuff.

OMG! thank you so much for sharing that information with us!

the alerts are always on for us! kindly regards from your followers!