In the last post, we discussed the tradeoffs in designing effective rules. Detection efficacy captures the needs of the consumer of your detection rules, because the persona can be more concerned with missing an alert (false negative) or having too many alerts that don’t matter (false positives).

Finding attacks is the core value proposition of what detection engineers do, and it’s what makes this field technically challenging. Although difficult, this work has an art and aesthetic that is hard to find anywhere else in security. This is because you aren’t solving a machine-to-machine problem, but a human-to-human problem, and the other human is unwilling to cooperate with you. To me, detection engineering and blue teaming, overall, are studies of behavior.

In this post, we’ll begin looking at how rules detect threat activity through atomic detections.

Detection Engineering Interview Questions:

What is the Pyramid of Pain?

What is an atomic detection rule?

Compare and contrast scenarios where an atomic detection rule can be effective or ineffective.

What is environmental context?

David Bianco’s Pyramid of Pain

Some attacks generate telemetry that is easy to identify as an attacker on your system or networks. Many attacks, however, require logic that depends on telemetry availability, environmental context, index windows of logs arriving at the SIEM, and understanding of attacker tradecraft or behavior.

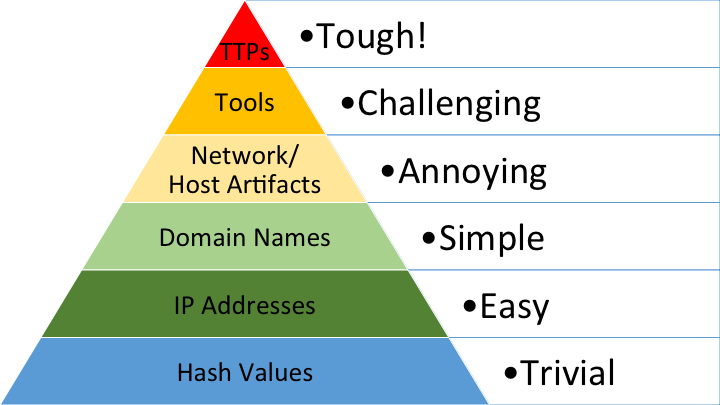

Much as detection engineers must consider operational costs when writing rules, threat actors incur costs when carrying out attacks. This cost-versus-cost battle helps frame attack and defense so you can impose as much cost as possible on an attacker’s operations, so they’re in so much pain they deem a tactic or technique not worth their time. This is where the “Pyramid of Pain” by David Bianco becomes a valuable exercise for security teams.

At its core, the Pyramid of Pain challenges defenders to focus on imposing as much pain on attackers. As you traverse the pyramid, operational cost to your efforts increases, but the amount of pain you cause to an attacker also increases. Each layer of the Pyramid represents an operational complexity for the threat actor to consider when staging an attack. The ideal state of detection is at the top: if you detect Tools executing in your environment, your detections are more robust because the order and context of the tool’s execution become irrelevant.

The best state is under “Tactics, Techniques and Procedures” (TTPs). This layer focuses on the behavioral aspect an attack. If you detect behavior of an attack, every layer below the pyramid become less relevant in your detection (for the most part), and the detection is robust enough to catch changes in Tools, Artifacts, Domains, IP addresses and hashes.

Imagine this: you write a rule that helps detect a known Command-and-control (C2) server you read from a blog post. You deploy that rule and it doesn’t find anything. Great, you aren’t compromised, and you’ll have great coverage for the future if there is a compromise.

Here’s the problem: threat actors are well aware that we find C2 servers, build rules, share with the community and blog about them. A C2 server is typically either an IP Address or a Domain. Have you ever rented a droplet on Digital Ocean, or bought a domain from Namecheap? You can spend a few dollars to rent more droplets or buy new domains. This requires minimal pain on the threat actor’s side, and defenders no longer block your new C2 server until it is discovered again.

Even worse, the IP address you wrote a rule for is now leased to a benign client, and it is now alerting on benign traffic, causing pain to you and your team.

So, how effective is your detection rule now? Not too effective! This is because detecting on a singular value, such as an IP address or a domain, is an Atomic Detection. Atomic Detections are narrowly defined rules that detect activity at a point in time with little to no context. Let’s dive into them in the next section.

Atomic Detections Lack Context

Atomic Detections are tactical in nature. They may seem precise in practice, but because they lack context from the environment and incur little pain for attackers, they become brittle and prone to false positives. As soon as an attacker changes their infrastructure or flips one bit in a new build of their malware, which changes the cryptographic hash value, your rule diminishes in quality.

Atomic Detections also exist for computer or network activity. The point here is that ignoring context in an environment, such as rules that don’t evaluate time signatures, environmental context, or regular activity, makes atomic rules risky to deploy.

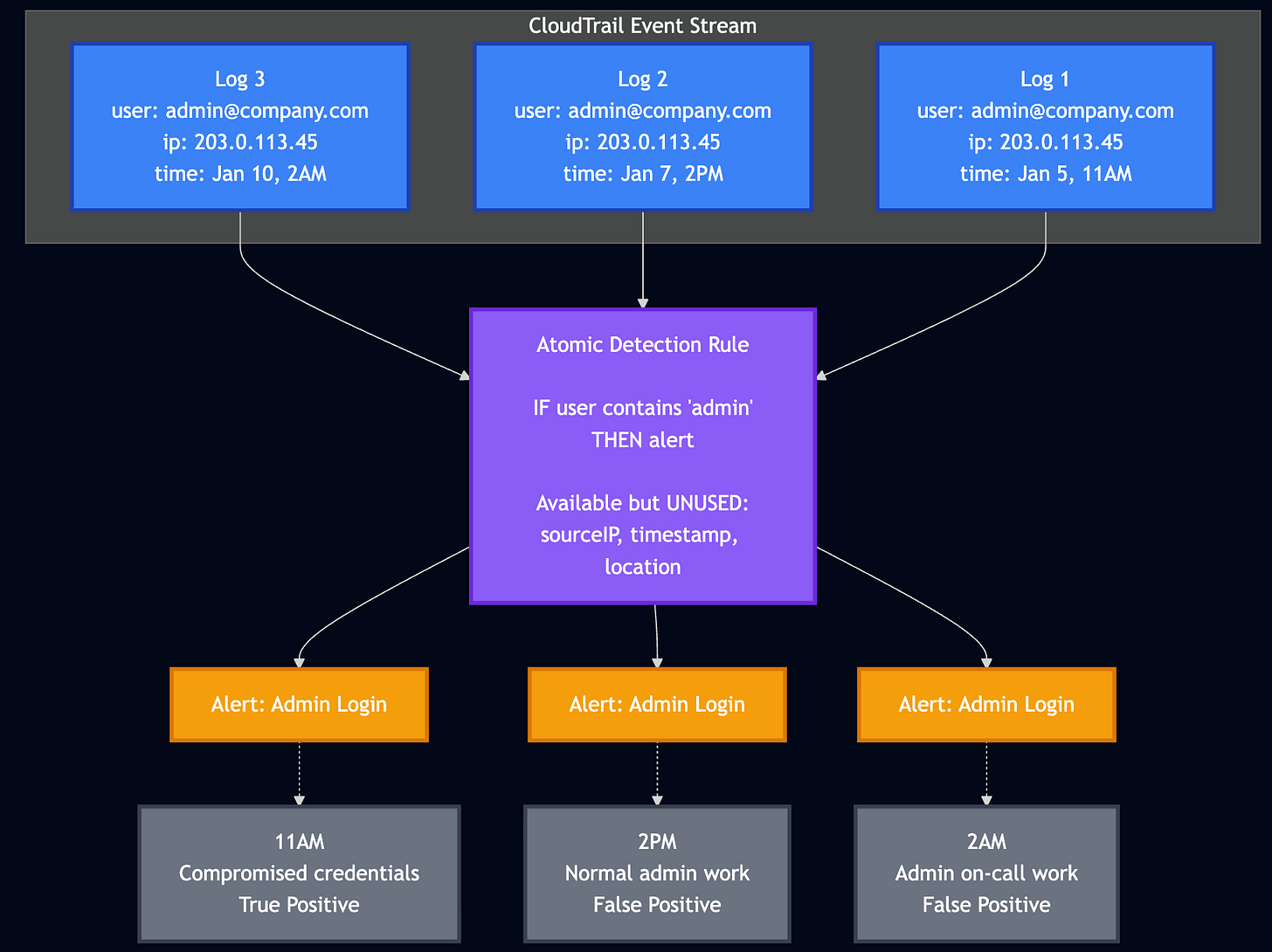

Let’s look at a basic alerting example with Amazon AWS Administrator login activity.

The rule is in purple and only alerts on Log activity where the user field value is admin. The SIEM correctly identities the user field containing admin three times . The 11AM alert is a true positive: the administrator credentials were compromised. The other two are false positives, indicating normal administrative work. To make things worse, the compromised login was during normal business hours.

So how do you differentiate between the three alerts?

You differentiate them by spending incident response cycles investigating each one. Now imagine 100s or 1000s of these being generated. The atomic rule strategy doesn’t work because there is little to no context on the event.

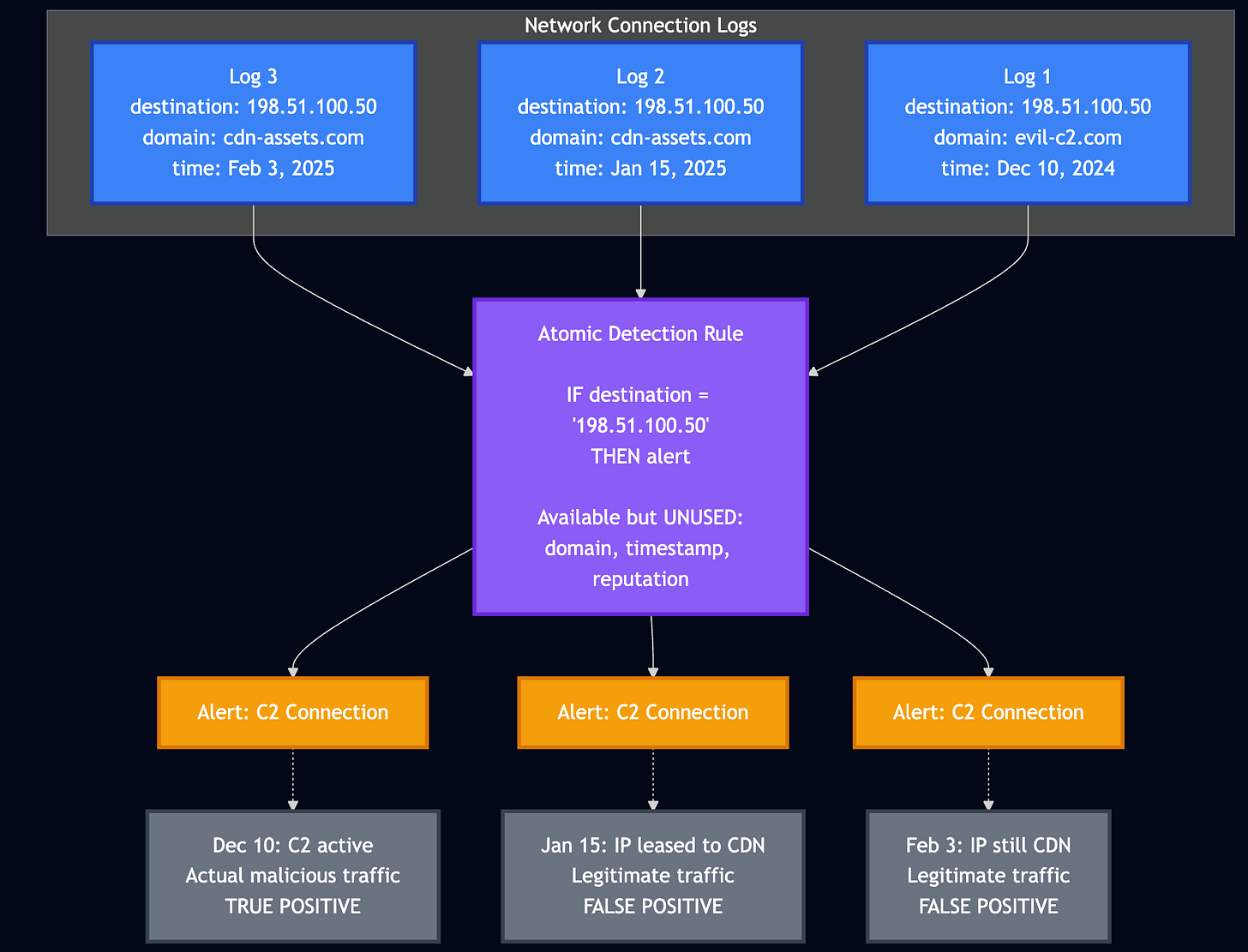

The same thing can be said for IP-based C2 alerting.

In this example, the detection engineer wrote an atomic detection rule for a known C2 IP address. Perhaps they read a blog some time around December 10 and added it quickly to find exposure. Log 1 enters the SIEM; the rule checks the destination field and generates a true-positive alert.

Fantastic! Let’s keep the rule!

The C2 was removed by the leasing company that owns it on December 11 due to the blog post. On January 15, a content delivery network leases an IP address, and network traffic logs flow through the SIEM, triggering an alert. Each subsequent network log afterward is a false positive.

The context from both of the graphs above is under the UNUSED field in the purple box. Associated domains, timestamps and physical location are all useful fields to add into the atomic rule to increase robustness of the rule and remove false positives. It would make sense, then, to start including all of these in your detection rule. Detection engineers need to understand the relationship between detection context and cost.

Imposing cost on ourselves

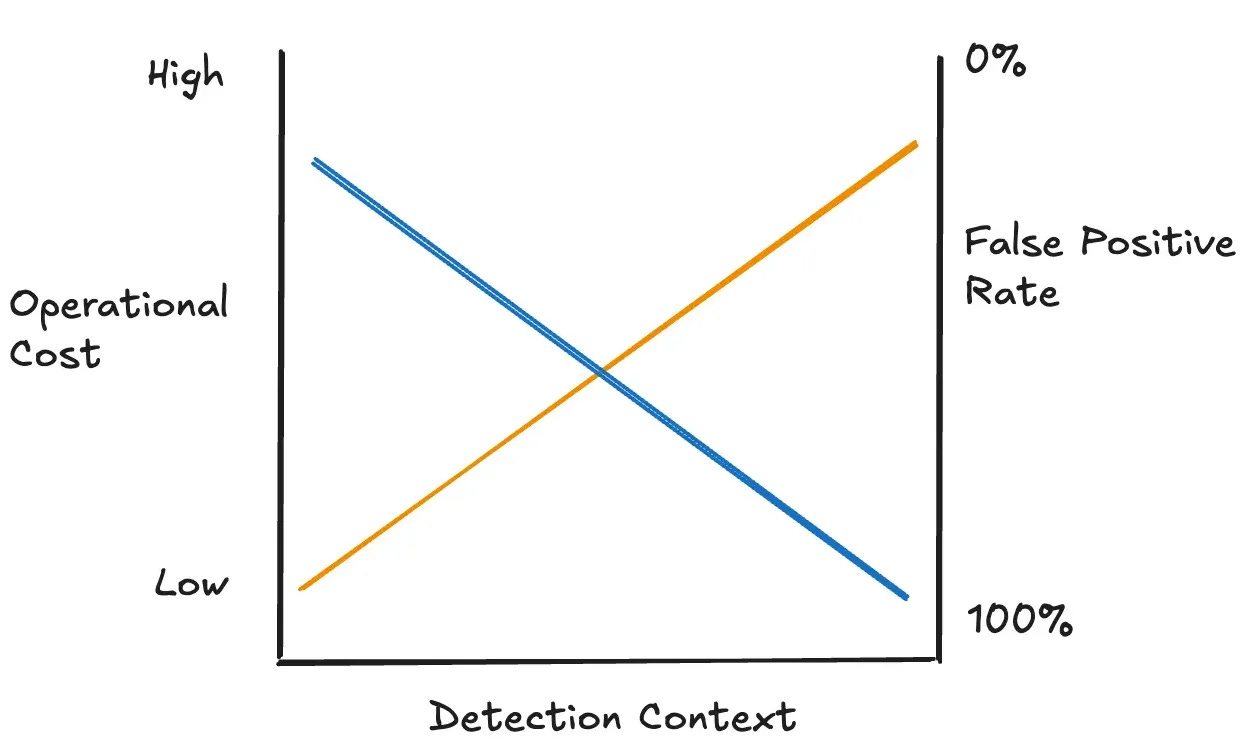

As we progress the Pyramid of Pain and add context to your ruleset, the cost increases. Cost can depend on time, resources, maintenance, or the technology needed to add context, such as threat intelligence. The following graph tries to explain this causal relationship:

At the bottom left, you could deploy a rule similar to the examples above. Because the operational cost of matching on a single value is low, the context is low. And because the context is low, the risk for false positives is high. As you add context (move to the right), the cost increases, but the false-positive rate decreases.

This is why not every rule can be perfectly accurate. There is a cost-benefit tradeoff, as well as information asymmetry from attacker behavior, that detection engineers must consider. The only way a rule can catch all threat activity is to alert on every piece of activity. That seems costly!

Conclusion

Atomic detection rules generally focus on low-context events or values. They can certainly help a blue team function, such as a SOC or a Detection & Response team, and they have a place in security operations. They risk generating many noisy alerts when the detection engineer fails to account for a threat actor’s behavioral patterns.

The Pyramid of Pain and imposing cost are industry-accepted concepts that help contextualize the competing objectives of blue teamers and threat actors. Writing rules to alert on the bottom parts of the pyramid, which primarily involve threat intelligence indicators (IP addresses, domains, hash values), imposes a greater cost on defenders than on threat actors. Defenders impose more pain on threat actors by climbing The Pyramid and writing rules that detect tools and TTPs.

For the next few parts of this series, I’ll explain the different ways detection engineers can write rules to capture threat actor behavior and the associated operational complexity.

Excellent framing of the cost-versus-context tradeoff. The AWS admin login example really drives home why single-value matches create investigation burden without environmental awareness. I've seen teams burn out chasing atomic detections that fire constantly on legitimate activity. The human-to-human problem framing is spot on, most blue teamers forget they're playing against adaptive adversaries not static infra.