DEW #145 - Modified Z-Score for Anomaly Detection, Watermarking for Audit Logs -> SIEM and Zack gives you all an RFC for homework

You must write "I will not write a detection rule for IP addresses" 1000 times

Welcome to Issue #145 of Detection Engineering Weekly!

✍️ Musings from the life of Zack:

I’ve been tinkering a ton with Anthropic’s Opus 4.6, and the agentic swarm mode is gratifying and terrifying to watch in action. I recommend trying it out!

My life the last two weeks have been sickness and travel. I got COVID before my office visit trip in NY (I went in negative!), came home, got a sinus infection 2 days later and I’m sitting here writing this with a fever. Go figure.

For those who watched the Superbowl: When the Patriots lose, America wins.

Sponsor: runZero

Master KEV Prioritization with Evidence-Based Intelligence

The CISA KEV Catalog tells you what to patch, but not how urgently or why it matters to your environment. 68% of KEV entries need additional context to prioritize effectively, yet most teams patch in order without understanding true operational risk.

A new KEVology report by former CISA KEV Section Chief Tod Beardsley reveals what KEV entries actually mean for defenders. Plus, the free KEV Collider tool from runZero helps you prioritize based on evidence, not assumptions.

💎 Detection Engineering Gem 💎

The Detection Engineering Baseline: Hypothesis and Structure (Part 1) by Brandon Lyons

Baselining is an overused term in this field because, at least in my experience, it’s a hand-wavy marketing term. You’ll read about a product that’ll perform baselines of your behavior and environment, and it’ll alert you if it detects something abnormal or outside that baseline. In practice, this works, but the opaqueness of some of these methods makes it hard to understand how it happens.

This is why posts like Lyons help cut through the opaqueness and show the receipts of how to do this in practice. And to be honest, it’s nothing groundbreaking, only in the sense that the concepts Lyons proposes here are part of entry-level statistics literacy. Which is why I’m pretty opinionated on the engineer of detection engineer. Don’t get it twisted: although the concepts in this post are entry-level statistics, understanding the application requires deep security expertise.

Lyons lays out a 7-step, repeatable process to establish a detection baseline, quoted here:

Backtesting of rule logic: Validate your detection against historical data before deploying

Codified thought process: Document why you chose specific thresholds and methods

Historical context: Capture what your environment looked like when the baseline was created

Reproducible process: Enable re-running when tuning or validating detection logic

Foundation for the ADS: Feed directly into your Alerting Detection Strategy documentation

Cross-team collaboration fuel: Surface insecure patterns and workflows with data-backed evidence

Threat hunting runway: When alert precision isn’t achievable, convert the baseline into a scheduled hunt

This process succinctly captures a well-thought-out detection process. Without data, how can anyone possibly deploy detections that will fire? Without context around that data, how can anyone possibly believe the rules that are firing outside of the baseline?

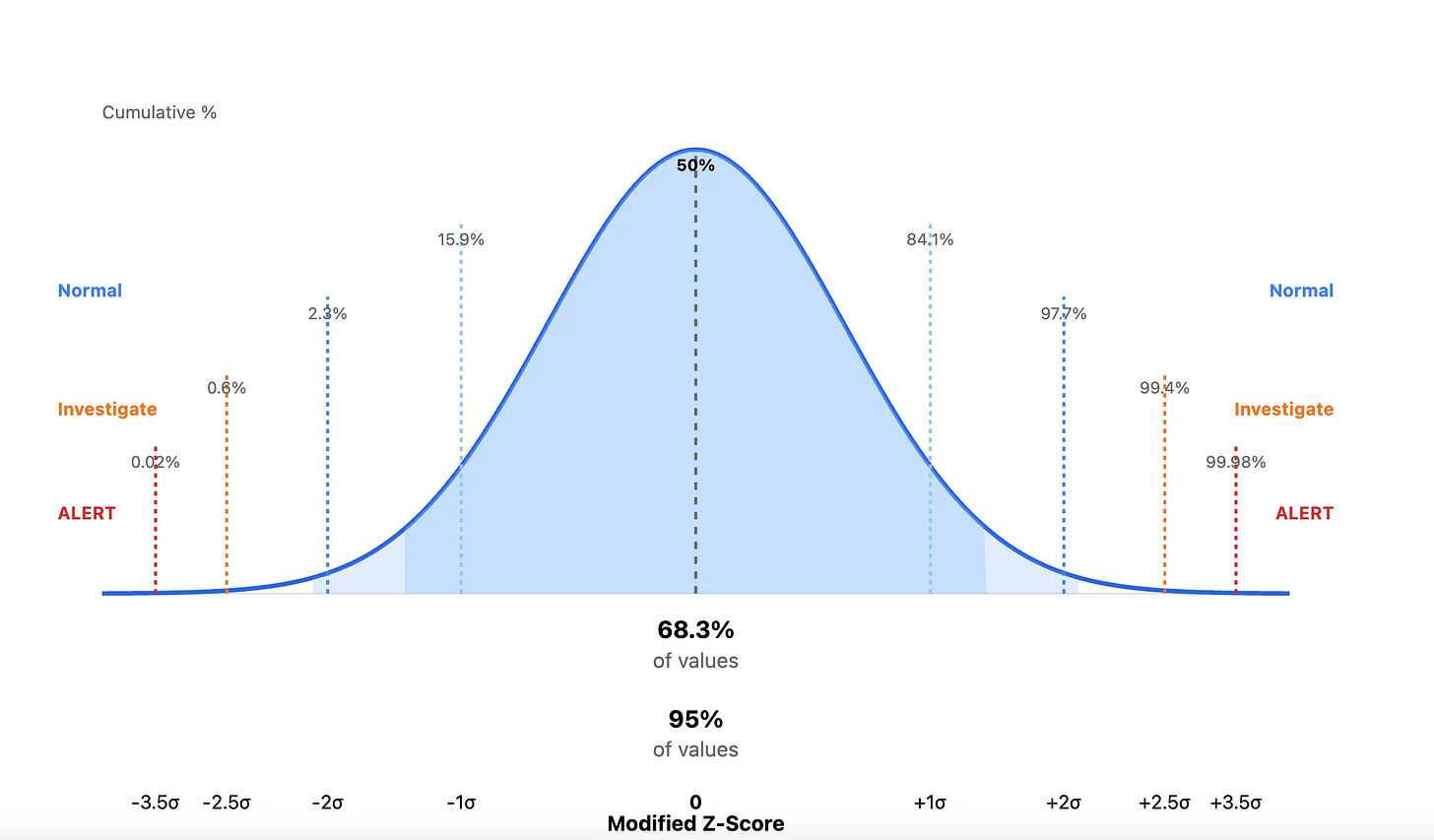

They step through the 7 steps here using a CloudTrail API example. Basically, Lyons tries to map out what anomalous behavior looks like for CloudTrail access across an environment. The statistics section focuses on a modified Z-Score. Here’s the rundown:

Security metrics (API calls per day, login attempts per hour, file accesses) approximate a normal distribution (a bell curve), especially when aggregated over time. This means that:

Most values cluster around the median (middle value)

Extreme values become increasingly rare as you move away from the center

The distribution is symmetric

To establish a baseline, Lyons collects historical data, such as 30 days of activity, and computes two key statistics:

Median - the middle value

MAD (Median Absolute Deviation) - measures spread around the median

When a new value enters your queue, you compute the Modified Z-score, which is the distance-via-standard-deviation of that value from the median. Modified Z-score is really good at capturing outliers, versus the regular Z-score, which focuses on standard deviations from the mean, and can be sensitive to outliers.

An outlier can be, according to Lyons, creating administrative credentials at 3am to an abnormal amount of S3 bucket accesses, perhaps used for exfiltration. Here’s a graphic I prompted Claude to create to drive this point home:

This type of rigor removes the guessing game about whether events are absolute measurements. Is 1000 API calls weird, or is 100? Is 10 pm an acceptable window for Administrator access, or is 5 pm? By looking at the standard deviations away from the median, you focus on relative measurement. It removes the human judgment about the absolute weirdness of an event, and whenever you remove a human from a large data problem, you get a bit closer to sanity.

Lyons created a follow-along Jupyter notebook with synthetic data to recreate the measurements in his blog. I’ll link that repository below in the Open Source section!

🔬 State of the Art

Building a Production-Ready Snowflake Audit Log Pipeline to S3 by xcal

Centralizing logs to your SIEM is a full-time endeavor, and requires expertise in so many areas, such as:

Data formats of the logs you are extracting, transforming, and loading into the SIEM

Telemetry source peculiarities, such as APIs, subsystems on hosts, or weird licensing issues

Choosing a technology stack that can normalize logs and send them into the SIEM

Navigating technological barriers due to inherent design choices, especially between data lakes or SaaS products

This is why I really enjoyed reading this post about moving audit log data from Snowflake into a SIEM. It focuses on the software engineering component of detection engineering, because many of the design choices made inside this post are things that you’ll hear about on a Software Engineering interview.

The first half of this blog details the design choices behind moving data from Snowflake to S3 and then to a SIEM, with clear architectural “gotchas” you need to design around. The most interesting one to me is the watermark strategy.

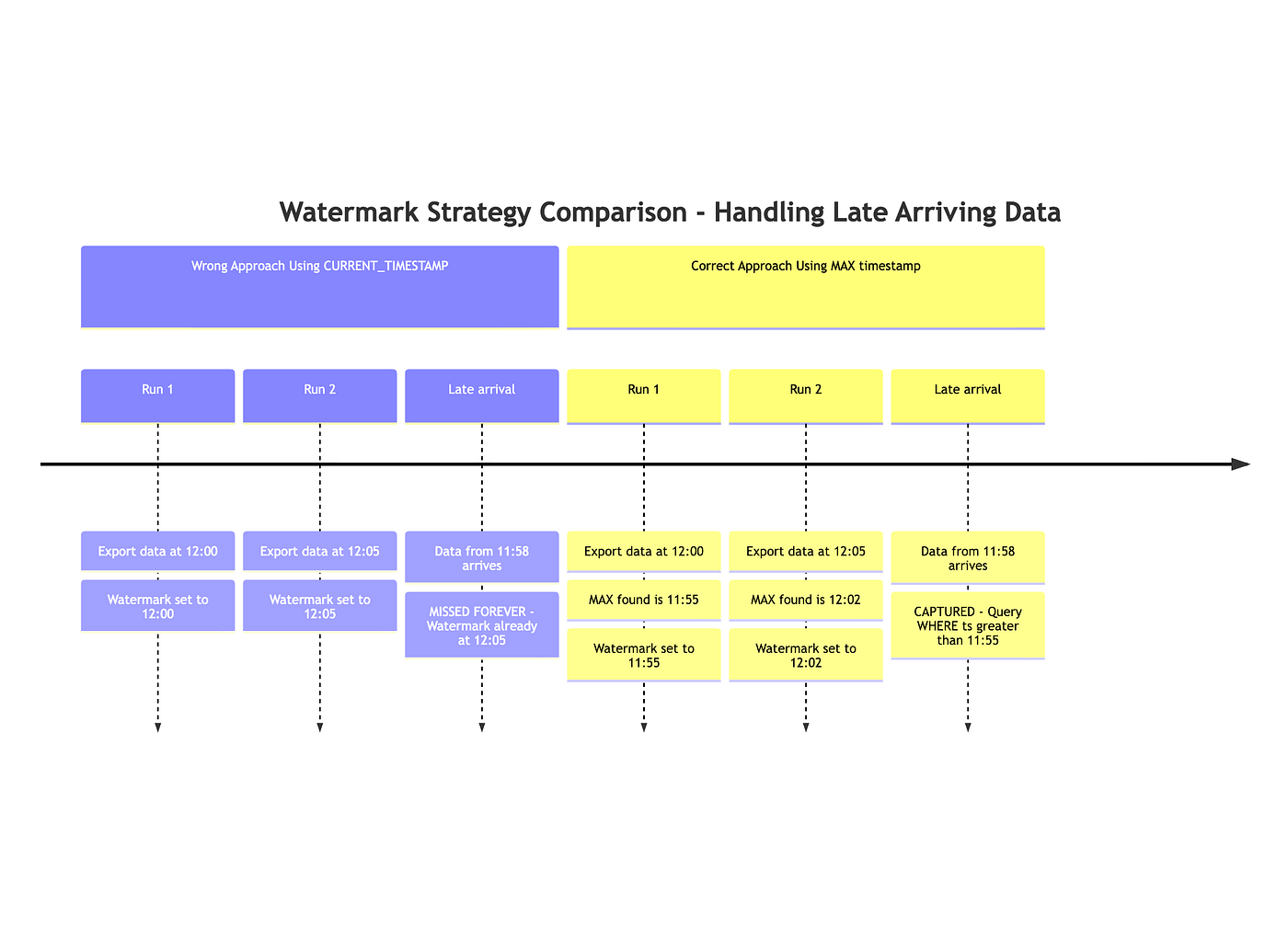

Snowflake audit logs have built-in latency. An event can occur at 12:00, but the audit log does not appear until 12:03. You use a watermark to pull the oldest events up to the last event you saw. For example, a watermark of 12:00 means you processed events up to 11:59. This watermark doesn’t work if you focus only on the timestamp generated, so you try to use it to focus on what you’ve observed.

In the purple example, 3 export runs for logs came in, and the watermark is updated based on the export time. When the “late arrival” log comes in, the watermark is later than the data's arrival time, so the log is lost forever. In the second yellow example, this is fixed by looking at the maximum observed time in the logs, not at the time the export is run.

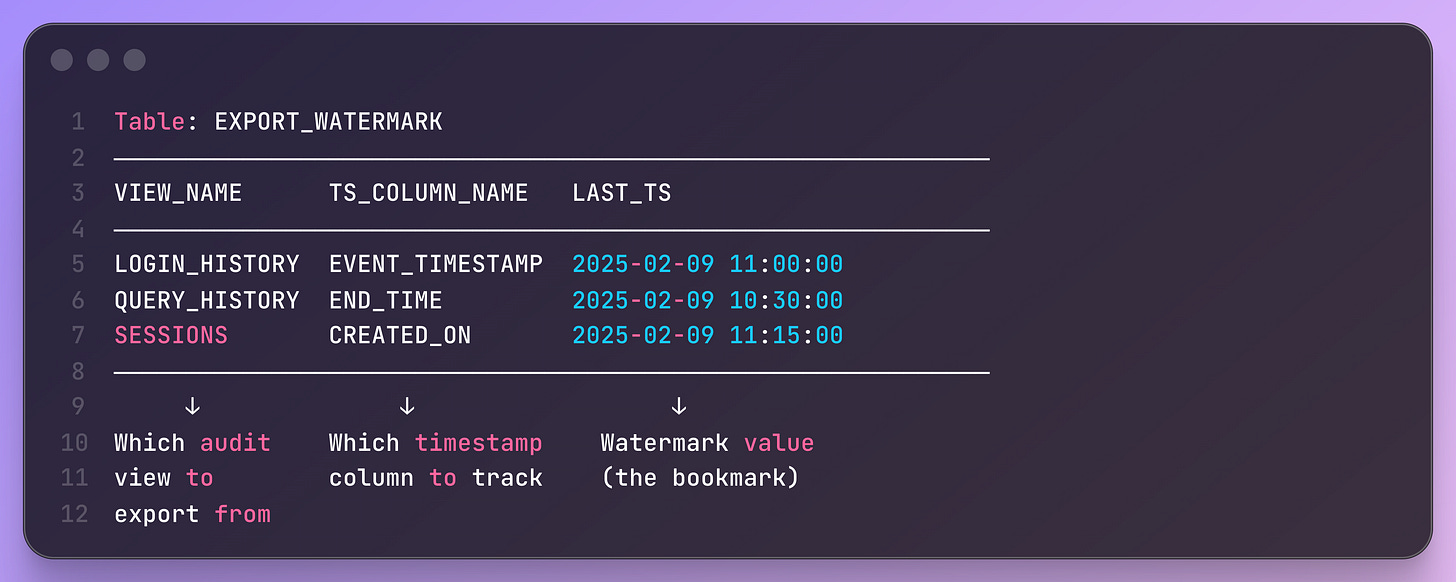

What’s beautiful about this blog, too, is how it sets up a “configuration-as-data” design pattern. They use a statically stored procedure for the export logic and a table that maps the target View, such as SESSION or LOGIN, to the timestamp used to perform the watermark.

This design choice makes it easy to add more views, VIEW_NAME, specify a target timestamp, TS_COLUMN_NAME, then store the watermark in LAST_TS. A singular INSERT into the EXPORT_WATERMARK table adds additional Audit logs views to export, without changing the code.

Detection Rule Fragility: Design Pitfalls Every Detection Engineer Must Know by SOCLabs

Detection rule fragility occurs when your rules become too precise for a single detection scenario and miss variants that achieve the same outcome. In this post, SOCLabs details several “gotcha” scenarios on the command line where classic detection on strings can be circumvented by operating-system-level trickery.

My favorite examples they list involve URL detection with cURL. There’s something about the concept of URL parsing that is so fascinating on the operating system level, because it’s a little known attack path that can have some hilarious results. For example, if you want some light reading, check out RFC3986 - Uniform Resource Identifier (URI): Generic Syntax.

Let’s say you write a rule to detect a local IP address, such as http://192.168.x.x Your operating system and browser parses it, and can navigate to it, so you write a rule to detect local subnet usage in cURL. But you can also write http://192.168. as hex, http://0xC0.0xA, or even octal, http://0300.0250. So, did you write a rule for those? :)

How I Use LLMs for Security Work by Josh Rickard

This is a cool, battle-tested approach by Rickard for prompting an LLM to do security work. I think people can become overwhelmed by what to prompt an LLM, because they are generally really good at taking vanilla prompt sessions and running with whatever work you assign them. But, as your work gets more complex, there are some nifty strategies you can use, and Rickard lays out, to make the best use of what they have to offer.

Giving context is probably the biggest takeaway here, so Rickard describes the concept of role-stacking, explains your technology stack, clarifies the current understanding of the ask, and gives it time to execute the ask.

What AI Really Looks Like Inside the SOC: Notes from a Fireside Chat by Daniel Santiago

In this post, Santiago shares his notes around a SOC fireside chat they attended during a Simply Cyber event. The cool part of his synopsis was seeing the “ground reality” of AI working and not working in a SOC environment. Most of the insights aren’t surprising to me, but it’s good to hear it validate some of our feelings. For example, Santiago points out how these agents raise the baseline for analysts, rather than replace them.

☣️ Threat Landscape

Beyond the Battlefield: Threats to the Defense Industrial Base by Google Threat Intelligence Group (GTIG)

The GTIG group published a large survey of threats they are tracking against Defense firms and organizations, such as contractors, critical infrastructure and government entities. They have four large takeaways and specify which threat actor groups are part of these takeaways:

Targeting of critical infrastructure by Russian-nexus threat actor groups to introduce physical and security effects

Hiring of fake IT Workers and DPRK’s focus on espionage using IT workers and malware campaigns

China-nexus threat actors representing the largest campaigns targeting these sectors by volume

An uptick of data leak sites and extortion groups against manufacturing firms that may supply the defense industrial base

VoidLink: Dissecting an AI-Generated C2 Implant by Rhys Downing

VoidLink is a post-exploitation and implant framework that focuses on cloud-native infrastructure. It was in the headlines around a month ago, and the main headline was that it was likely LLM-generated. Downing pulled apart the payloads and tried to confirm this finding, so it’s nice to see proof rather than believing the hype. The fun part is that within the binary, several clues suggested it was LLM-generated, primarily in the code comments.

According to Downing, and I tend to agree here, adding comments to your malware seems like a rookie move because you want operational security and anti-research capabilities, so this likely suggests it’s LLM-generated and the operators were careless.

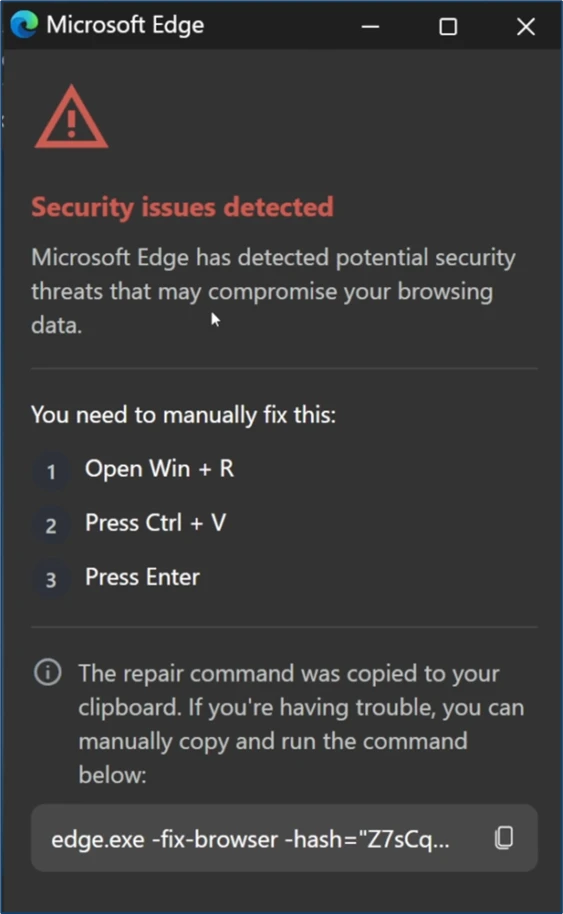

New Clickfix variant ‘CrashFix’ deploying Python Remote Access Trojan by Microsoft Defender Security Research Team

Microsoft Security Research uncovered a new style of ClickFix social engineering techniques, dubbed CrashFix. When a victim is funneled to the malicious site, they are tricked to thinking their computer is crashing, and are directed to run the malicious payload.

The rest of the campaign is well-researched, but nothing particularly different from other ClickFix and infostealer campaigns. I imagine we’ll continue to see these social engineering threats evolve until we blow up command-line access for people and move to something else. Perhaps Claude Cowork social engineering?

Malicious use of virtual machine infrastructure by Sophos Counter Threat Unit Research Team

This piece by the Sophos Threat Research Team began with a security incident in which they uncovered attacker infrastructure with unique Windows hostnames. When the team dug into these hostnames, they found they were out-of-the-box names from a legitimate IT provider, ISPSystem. At first, it seemed like a single actor was leveraging ISPSystem to quickly deploy infrastructure, but when the team pivoted to Shodan, they found several thousand instances of ISPSystem infrastructure in use across many different malware campaigns.

Windows hostnames are a cool pivot that I haven’t really seen much of in my years of threat research. This worked in Sophos’ favor because it’s virtual machine software that offers some ease of use for several threat actor groups.

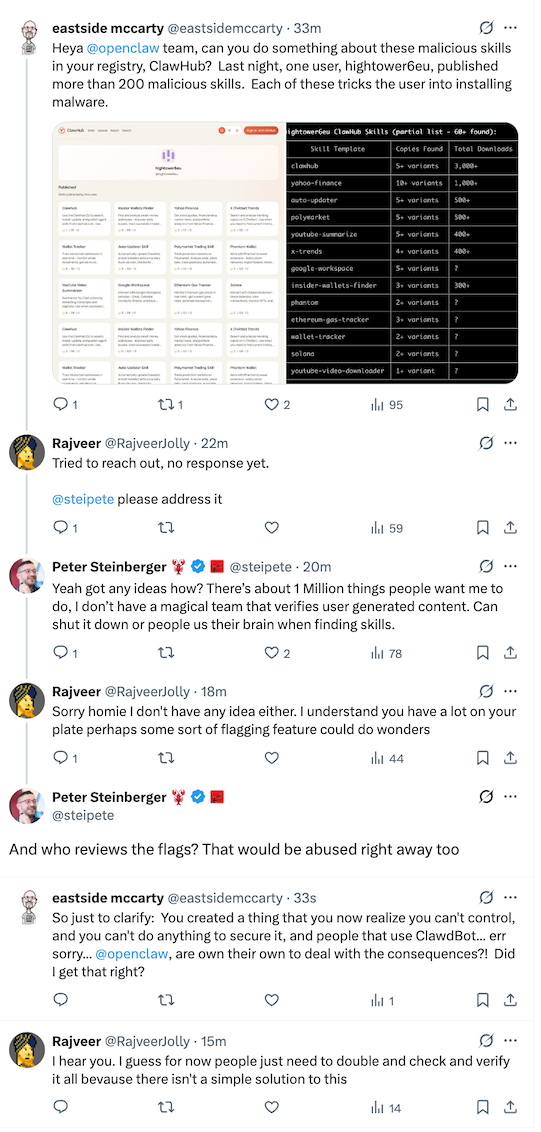

ClawdBot Skills Just Ganked Your Crypto by Open Source Malware

This ClawdBot malware post is a little different from the VirusTotal one I posted last week, mostly because it shows some of the conversations to the creator of ClawdBot on X on removing them. Hint: it doesn’t look good, and you should avoid using these skills registries until they get much better security and governance practices in place.

🔗 Open Source

Btlyons1/Detection-Engineering-Baseline

Link to Brandon Lyon’s modified Z-score lab listed above in the Gem. Contains a Jupyter notebook to help readers follow along, as well as loads of synthetic data to try out the detections.

moltenbit/NotepadPlusPlus-Attack-Triage

PowerShell cmdlet to test if you ran a compromised version of NotepadPlusPlus from their incident announcement last week. It checks known IOCs, so it’s not a guarantee that they are still relevant or that a clean run means you weren’t compromised.

This is a clever technique that abuses Windows ProjFS. ProjFS allows processes to project filesystems based on several attributes, so it’s used for things like OneDrive where you connect out to a drive hosted on a cloud provider. S1lkys built this in a way that it’ll project an encrypted payload, like Mimikatz, if it detects a source process coming from the command line versus EDR tools.

Wardgate is an Agentic proxy that stores secrets and API keys on your agent’s behalf. The idea here is that the Agent is aware it has API access to some external service, you have it use Wardgate, and Wardgate will serve as the API proxy. This is especially helpful if you are afraid of attacks on Agents that steal local or cached credentials.

August is an LLM penetration testing harness that integrates with dozens of LLMs. It has hundreds of attacks in 47 attack categories that you can let loose on models you are using from foundational labs, or some that you are training on top of the foundational models.