DEW #142 - Slack's Agentic Triage Architecture, Detection <3's Data and Sigma evals

bills lose and now the team's imploding

Welcome to Issue #142 of Detection Engineering Weekly!

✍️ Musings from the life of Zack:

I’m not usually a person who does New Year’s resolutions, but I’ve committed to small changes that have already made a positive impact in my life.

Using a notebook to take notes and to-dos at work

Meditate on Headspace for 4 days a week

Playing video games twice a week. For some reason, I’m back on Dota2 so I’m sure that’ll be helpful for my mental health

There’s a 50/50 chance I’ll make DistrictCon this weekend :( There’s a massive snowstorm hitting Washington, D.C., and as a former Marylander, I can tell you that part of the country cannot handle snow

I’ve been messing with local MCP server development via stdio and HTTP APIs, and I’m starting to shill Claude Code to everyone I talk to. It ripped through a malware analysis at work a week or so ago, and we were able to hunt for IOCs in under 5 minutes.

💎 Detection Engineering Gem 💎

Streamlining Security Investigations with Agents by Dominic Marks

In the age of AI SOCs, it’s still hard to understand where the concept of agentic triage fits into everyday operations. Products tend to present the problem set and solutions in a clean, understandable way. This is a good thing - having a product company frame the space in clear, concise benefits and downsides drives the decision by the security operations team about how much cost they incur in building or buying one.

Blogs like this are showing why our industry is awesome with transparency. Slack's security operations team published its work on building an in-house agent-based triage system. You see many of the same principles and concepts across products, but because there is no moat or trade secrets to protect, there’s a lot more to dig into.

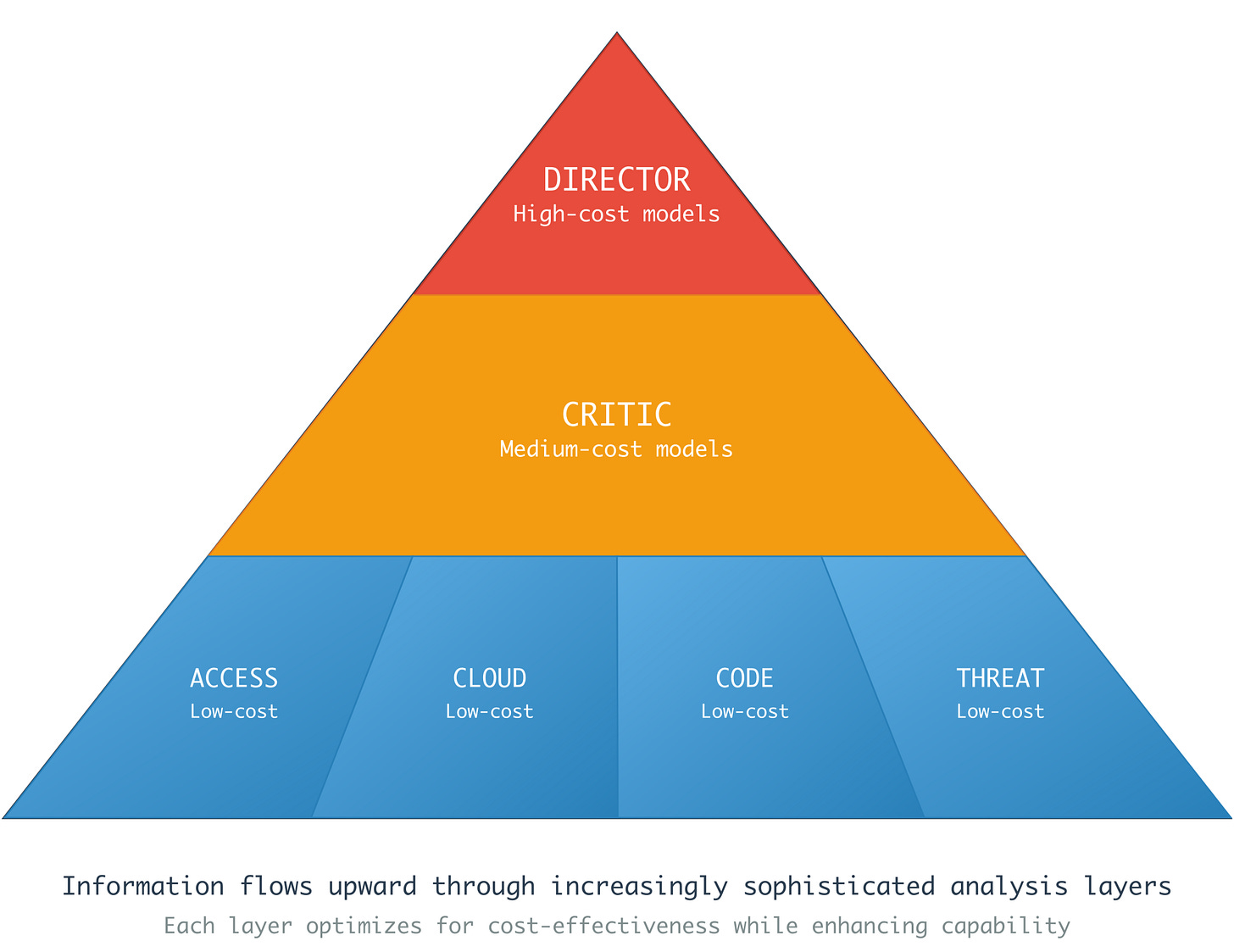

What you see above is their approach to their agent-to-agent orchestration system. The top of the pyramid starts with a director who leverages high-cost models. Thinking models that tend to take their time and deliberate on prompts and results. This makes sense from a planning and analysis perspective.

The critic biases itself to the interrogation of individual analysis from telemetry and alerts. It doesn’t require as much model cost, but it should spend a reasonable amount of time challenging assumptions and analyzing the lower-cost model. It presents the amalgamation of data and investigative output back to the director. The Director is probably thinking mode models, where you spend the most money on tokens to understand whether the bottom parts of the pyramid performed their job correctly. This is the gate between a human and the system, so you want only high-quality analysis moving forward.

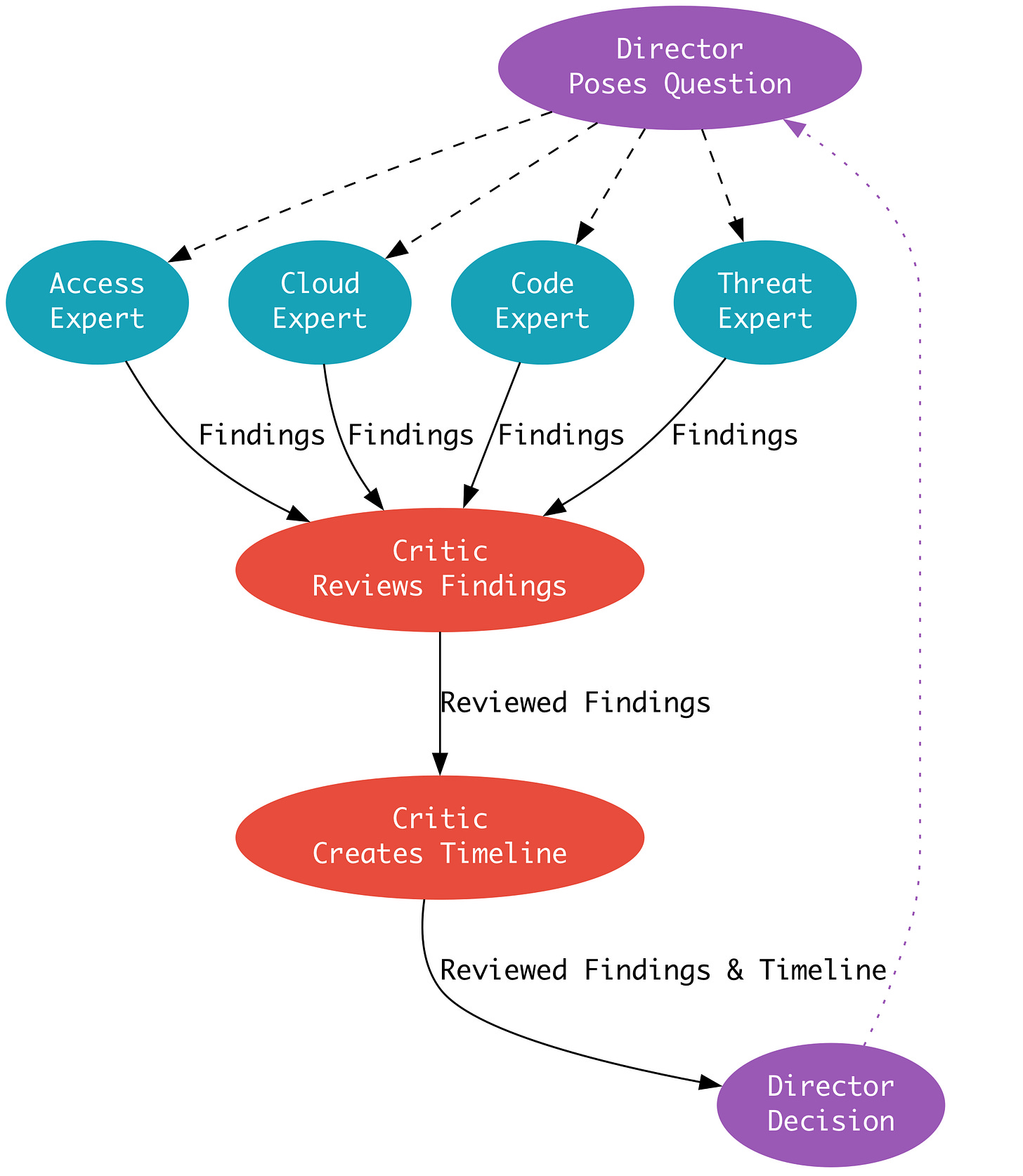

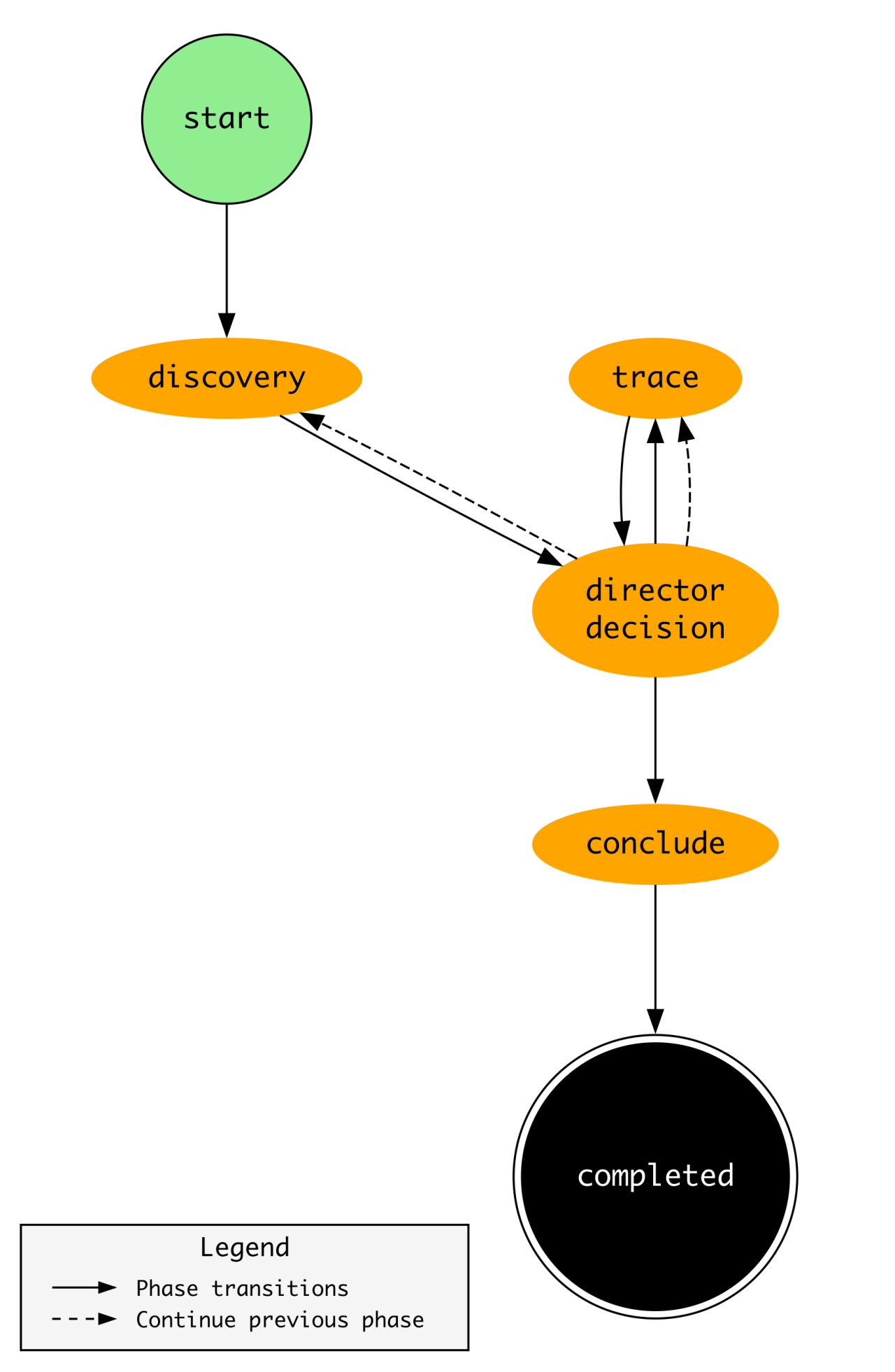

The phase transition diagram is super interesting because it puts the above “Director Poses Question..” investigation step into practice.

According to Marks, the Director makes decisions for each part of the phase to see whether it needs to close the investigation or continue it further. The “trace” component is where the Director engages an expert within their architecture to perform additional investigative analyses.

Honestly, it’s hard for me to provide my own analysis here, because the blog is just so complete. So, if you are a person who is skeptical of these types of setups, borrow or steal ideas from this Slack blog and try it on your own. It seems reasonable, and if the idea is that you perform 5 investigations that take 2 hours each, it reduces 3 of them from 2 hours to 10 minutes, and it catastrophically fails on 2 of them, you still saved 6 hours!

🔬 State of the Art

Data and Detect by Matthew Stevens

This post by Stevens dives a bit deeper into the concept of detection observability. In our field, we tend to focus on the research element of rules and detection opportunities, but leave much less conversation about data quality. Remember, there is no rule without telemetry, and there is a concept Stevens points out around data usefulness that I think demonstrates this point perfectly.

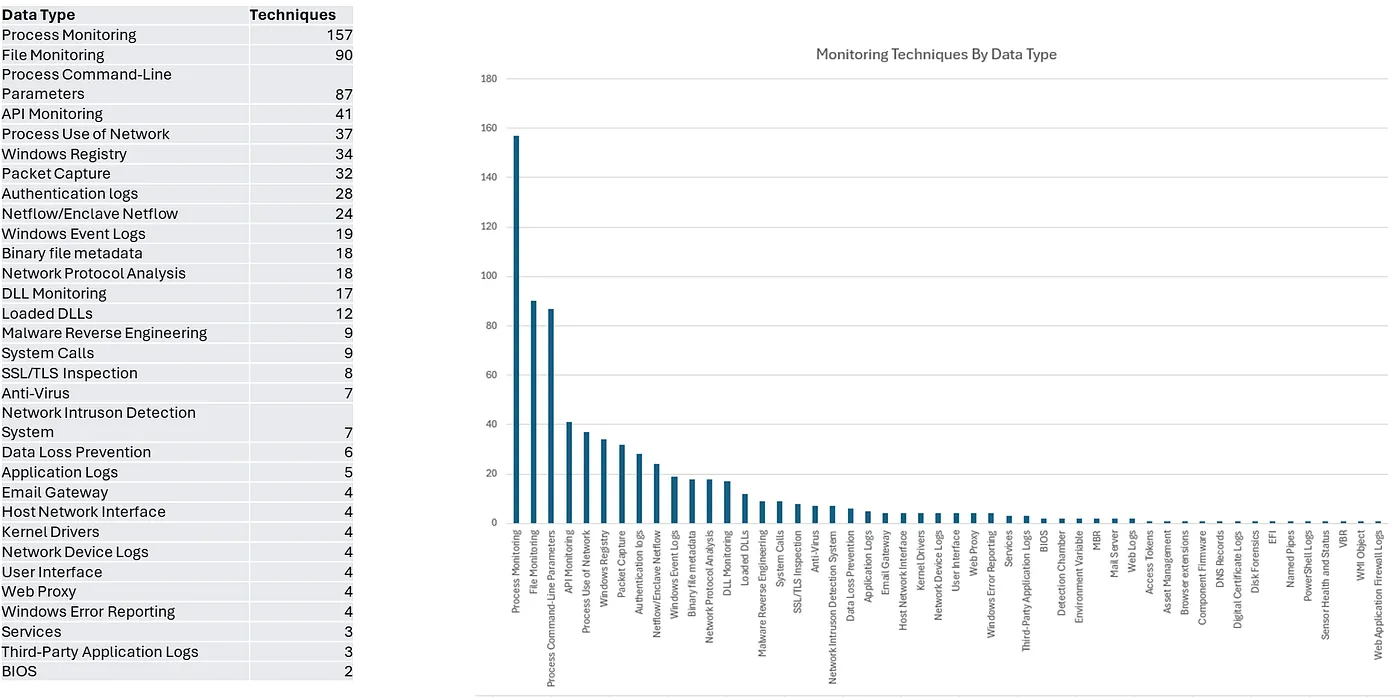

Not all sources are the same when it comes to individual atomic qualities for alerting, but when you map them to techniques, you notice that the composite qualities (a sum of many data sources finding an attack chain) become crucial. The graph above, generated by Stephens, shows how important Process Monitoring is for data usefulness. In fact, without Process Monitoring, you lose close to 30% of the techniques you can combine with other data types to alert on.

They also comment on how hard it is to build schemas and normalize telemetry so your teams can operate out of a common lexicon of writing rules. This highlights that a large swath of issues we should deal with it focus heavily on the software and data engineer components of our jobs as equally as the threat research components.

Sigma Detection Classification by Cotool

Continuing Cotool’s research on security AI agent benchmark performances, they setup a website for studying performances on their benchmarks and released a new one on Sigma Detection classifications. The goal of this benchmark was to assess how well foundational models were trained on attack tactics and techniques. The Cotool team fed the full Sigma corpus to 13 foundational models and stripped the MITRE ATT&CK tags to see if they correctly mapped the tags back to the original rule.

Claude’s Opus and Sonnet 4.5 performed the best overall with the highest F1-score and but also the highest cost, ~somewhat similar to what we saw in their last benchmark on the Botsv3 dataset. The team provided their analysis of these placements, their prompts and tradecraft behind the evaluation, so others can run the same benchmarks as well.

5 KQL Queries to Slash Your Containment Time in Microsoft Sentinel by Matt Swann

I have a biased view on what is and what is not a detection rule. Even to the point where I’ve reduced the concept of rules down to one definition: a rule is a search query. There is a rationale behind it: SIEMs and logging technologies require a search query to generate results. But, as I break out of my bubble, I notice that not all search queries have the same value from a detection point of view.

In this post, Swann demonstrates this concept through the lens of a Security Incident Responder. When your goal is containment rather than accuracy or a balanced cost of alerting, accuracy matters less because the goal is to use your analysis skills to find and kick out threat actors as quickly as possible. Swann provides readers with five high-value KQL queries to help responders quickly orient around a potential intrusion. The cool part here is their unique experience in this field, even noting that some queries led to the discovery and containment of an active ransomware actor.

👊 Quick Hits

Detection as Code Home-Lab Architecture by Tobias Castleberry

I love seeing home-lab setups because there are many ways to set up an environment to practice advanced concepts with open-source and free software. This blog is part of a series by Castleberry where they document their journey from an analyst to a detection engineer, and they showcase some of their expertise and how they’ve learned along the way.

Building your own AI SOC? Here’s how to succeed by Monzy Merza

Speaking of demystifying AI SOC and agentic security engineering from Marks’ Gem listed above, this blog by Merza provides an irreverent commentary on the state of building these architectures. There are some non-negotiables Merza points out, such as data normalization, the concept of a “knowledge graph”, and honing foundational models and giving them the right instructions rather than relying on them out of the box.

The Levenshtein Mile by Siddharth Avi Singh

Before the age of LLMs, there was a ton of research and implementation of some pretty clever mathematical techniques to find and detect on threats. I used to work for a threat intelligence product company that specialized in detecting phishing infrastructure, and one of the key elements of finding phishing is understanding what the victim organization owns, so you can see how threat actors try to abuse and socially engineer its customers.

In this post, Singh details the Levenshtein Distance algorithm. The basic premise here is that you can measure the similarity between two strings and generate a score. If that score exceeds some threshold of similarity, you can generate an alert to an analyst and investigate whether or not it is phishing. Domain names are the logical data source here, and you can review them from the public domain registries, DNS traffic, or the Certificate Transparency Log and try to proactively block them before they become an issue.

☣️ Threat Landscape

After the Takedown: Excavating Abuse Infrastructure with DNS Sinkholes by Max van der Horst

This post by van der Horst helps readers understand what happens after a domain is sinkholed. We typically see news stories about a large botnet or ransomware operation being taken down, and the takedown includes seizing domain names used for command-and-control communications with victims. High fives and good vibes happen and then we focus on the next big thing.

van der Horst challenges this finality and tries to argue that a sinkhole is more than just an interruption operation; it’s also a forensic artifact that helps discover more victims and additional malicious infrastructure. They downloaded several datasets, combining passive DNS and open-source intelligence feeds, to understand the rate of disruptions and how to perform temporal analysis of these takedowns to discover unreported infrastructure.

It also allows analysts to cluster activity and create new detections as new botnets or campaigns emerge, where many cases involve the reuse of code and infrastructure techniques.

How to Get Scammed (by DPRK Hackers) by OZ

This is a great article showing an individual infection chain done by a Contagious Interview threat actor. OZ accepts the bait on Discord and walks through how the DPRK-nexus threat actor tries to infect him by taking a malicious coding test. OZ brings receipts: there’s a lengthy Discord conversation where the threat actor prods OZ and eventually convinces them to apply for the job.

There’s some cool analysis with cloning the repository and using docker and pspy to inspect the malicious traffic.

What’s in the box !? by NetAskari

NetAskari, a security researcher, stumbled upon a Chinese-nexus threat actor’s “pen-test” machine and managed to download a bunch of their custom tooling for analysis. The Chinese hacker ecosystem is in a bubble, the result of both cultural and artificial barriers imposed by the PRC. These barriers create opportunities to build tooling, exploits, and software in a silo, so when you find a goldmine of tooling available for download, it’s always great to download it and see how other hackers are performing operations.

They found a litany of post-exploitation tools, some of which are custom-written and look similar to the likes of Cobalt Strike or Sliver, a bunch of custom Burp Suite extensions, and some malware families, like Godzilla, that were used in nation-state operations against the U.S.

Dutch police sell fake tickets to show how easily scams work by Danny Bradbury

I think phishing simulations at a professional organization is lame, but I actually think it works at scale against the general populace as a form of education. Apparently, the Dutch Police thought the same. They set up a fake ticket sales website and bought ads to trick victims into visiting and purchasing tickets for sold-out shows.

Tens of thousands of people visited the website, and several thousand people bought tickets, which is a wild stat if you want to steal some credit cards. Obviously, the Police did not steal credit cards; they used them as an educational opportunity to help folks understand the risks of online ticket fraud.

CVE-2025-64155 Fortinet FortiSIEM Arbitrary File Write Remote Code Execution Vulnerability by Horizon3.ai

From the blog:

CVE-2025-64155 is a remote code execution vulnerability caused by improper neutralization of user-supplied input to an unauthenticated API endpoint exposed by the FortiSIEM phMonitor service. Oof. I couldn’t tell any of you the last time I’ve seen remote code execution vulnerabilities in SIEM technology.

The specific service, pMonitor, listens on 7900. It serves as the control plane for these devices, much like the Kubernetes control plane, and supports orchestration and configuration API calls. I ran a quick scan of likely FortiSIEM devices on Censys and found over 5000 publicly facing servers.

This blog has some details on the vulnerability, and, as with most FortiGuard and edge device vulnerabilities, user-supplied web request data with complex string parsing leads to a command injection deep within the application code.

🔗 Open Source

MHaggis/Security-Detections-MCP

Locally run MCP server for detection engineering. Leverages stdio transport so nothing leaves your machine which is always good if you are writing rules or queries in a sensitive information. It exposes 28 tools where a local LLM client (Claude, Cursor) can look at detection coverage, MITRE classification, KQL queries and data source classification.

PoC of an LLM exploit generation harness. The README has an extensive background on how they approached benchmarking Claude Opus and GPT 5.2 with no instruction on how fast they can analyze a vulnerability and generate exploit code. They introduced several constraints in test environments to challenge the models, such as removing certain syscalls, adding additional memory and operating system protections, and forcing the agents to generate an exploit with a callback.

tracebit-com/awesome-deception

Yet another awesome-* list on deception technology research, open-source repositories and conference talks.

mr-r3b00t/rmm_from_shotgunners_rmm_lol/main/mega_rmm_query.kql

This repository caught my eye because I’ve never seen a rule that started with the word “mega”. And when I mean mega, I’m thinking a few hundred lines for something pretty complicated. But this RMM detection query rule is 3000 lines long. Can you imagine needing to tune this?

This is a clever phishing simulation platform that abuses iCalendar rendering to deliver legitimate-looking phishing invites. It leverages research from RenderBender, which abuses Outlook’s insecure parsing of the Organizer field.